"I dig into the most fearsome parts of myself"

Edition 39: An interview with artist Alex Gingrow

Alex Gingrow sounded delighted as she described to me how, as a kid growing up in Tennessee, Alex loved to dig through the trash and find old onions to play with. “It was so satisfying to peel back the layers. The outside would be so gross and slimy, and inside there was still a fine little onion that you could use. It’s a great metaphor for the complexity of human beings,” said Alex, smiling at the memory.

This anecdote about finding beauty in the trash and relishing unexpected juxtapositions — yuckiness and sweetness rubbing up against each other — sums up what drew me to Alex and her work. Here is a pretty, blonde, Southern woman who creates art that punches you in the face with its brutal honesty about how people treat each other, and the societal hypocrisies we tolerate, painted in exquisite ink detail.

I love that Alex is not all that she first seems. Behind the warm embrace and twinkly eyes, there’s a fizzing pot of political outrage, gritty resilience and artistic ambition. We first met through our young daughters at summer camp, which is how I meet most new friends these days. When I arrive for the interview, we walk past a pile of mulch on the lawn and get settled in the sunlit art studio at the back of her family property in Kerhonkson, NY; a space which Alex shares with her husband, artist Michael Scoggins.

I am there to interview Alex the artist. But before we start, we have a conversation, mom to mom, woman to woman, about the challenging twelve months that Alex and her family have been through. Last year, Alex lost her father; and his death was closely followed by her daughter Scout’s diagnosis with a rare genetic abnormality that led to major surgery this summer and a permanent shift in their everyday lives and future plans. Alex has barely been in the studio for over six months. She hasn’t had the bandwidth to create; other roles had to come first.

And yet, Alex the artist persists. She knows that she is capable of many things, and many people rely on her, but, Alex says, “If I don’t do art, I can’t do the other things.” So, Alex writes. She walks. Sometimes she stares at the tubes of ink in front of her or the corner of the studio and thinks about sentences or color combinations. Like many creative women faced with an overloaded equation of responsibilities that simply cannot add up, Alex is trying to give herself grace to be less perfect, because mistakes can be a kind of perfection too. And when she is able, Alex steps into the studio and embraces the freedom and the structure that art provides: “I process everything in here, in the studio — being in a space where I can dig to the deepest, darkest, most fearsome parts of myself. I love having that mandate.”

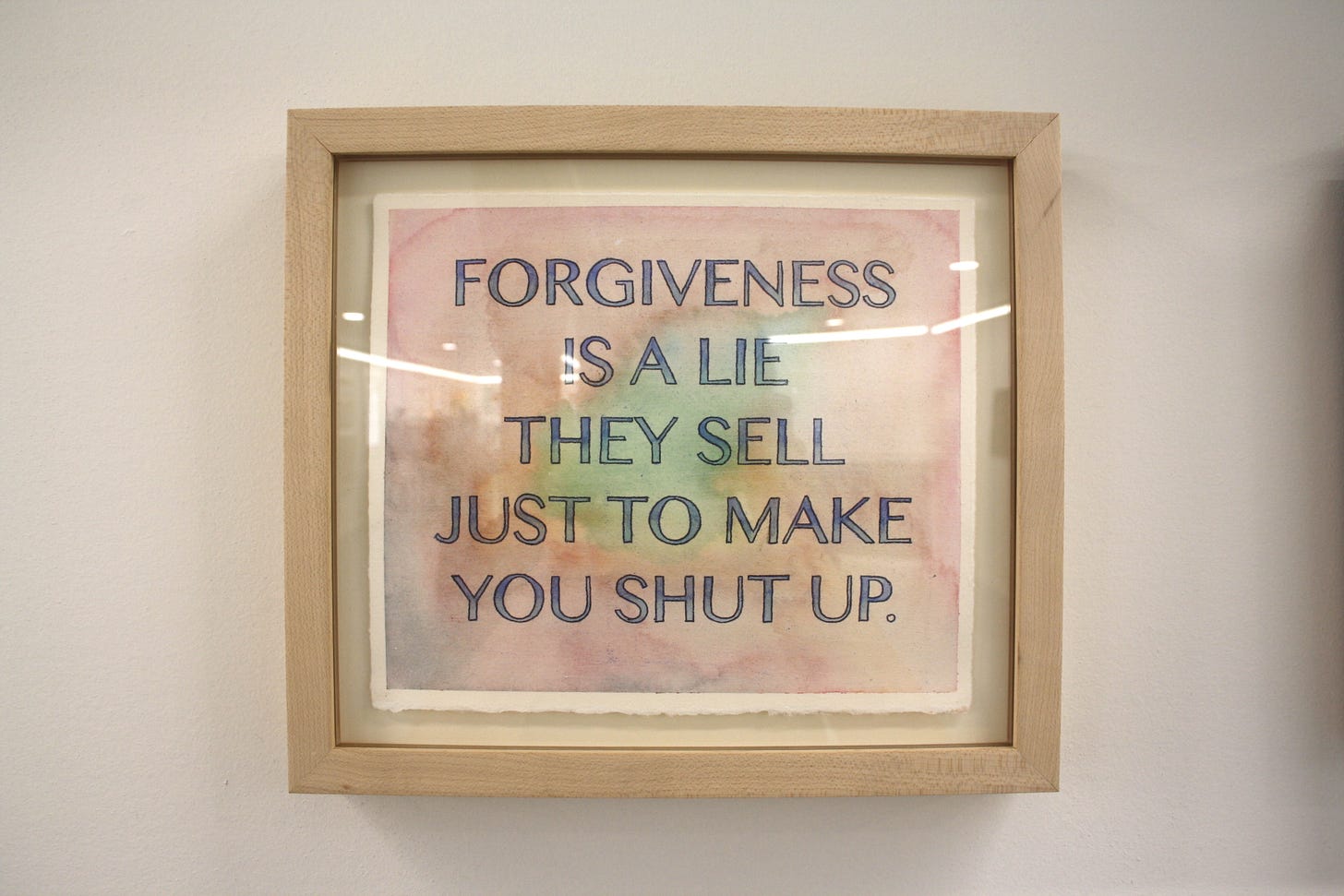

Adversity has not quashed Alex’s wry take on life — she is still funny as hell. The twisted humor of her word-driven artwork caught my eye when I first saw it at an open studio event as part of Upstate Art Weekend. Her paintings seem to have a compulsion to confront us with our worst selves in ways that feel just tongue in cheek enough that you desire the affront, and don’t reject it. Phrases she has chosen to elevate into artwork include “Forgiveness Is a Lie They Sell Just to Make You Shut Up” (rendered in delicate pastels) and “Okay Fine But I’m Not Changing My Fucking Name” (from the Karaoke Challenge Series.) The Provenance Label Series that grabbed attention in the art world was a controversial recreation of real, callous utterances overhead in early-aughts New York galleries, where she worked as a framer while building her portfolio; for example: “Which one was damaged? The unsold one. Oh, that’s fine. Nobody cares about that one anyway.” In another series Alex painted verbatim quotes of President-elect Trump from the infamous ‘Access Hollywood’ / “grab em by the pussy” video that originally surfaced in 2016. One gallery in Georgia shut down a show of those paintings early for fear of backlash, while the person who literally said the words they depicted sat uncensored in the White House.

Alex is many things. Most certainly talent rich and time poor. And, despite everything going on in her life, Alex is kind. She invited me in, gave me a seltzer, and let me pick her brilliant brain for two hours of her precious studio time. I hope you love hearing about her journey as an artist as much as I did.

AJ Lee: Let’s start at the beginning, Alex. Where did you grow up and how do you think that has influenced you?

Alex Gingrow: I grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee. I was in this progressive bubble. My parents split when I was just two years old, both bleeding heart Democrats. It was a queer family: my Mom started dating women when I was 15 or 16 years old; my aunt is gay.

You learn to get along [in a conservative environment]. To play along when you need to and educate when you’re able, advocate. I was always considered weird and different but I had a good time — even as a young kid I knew I didn’t belong. But I was a cheerleader, I had great friends, we partied like crazy. There’s many things I love about being from the South: the warmth of character, the Southern gothic, the food (not the meat kind)... but I don’t want to ever live down there again. The political climate keeps us away from there. It was always present but now it's dangerous. You can’t speak up because someone could shoot you. The folks who stayed in Tennessee, it’s either Jesus or drugs, and I’m not interested in either. Well, maybe one more than the other.

AJL: So, what led you to pursue being an artist?

AG: I don’t think I had a choice. In undergrad, I was an English Major — my final class was Virginia Woolf class, one novel a week! It was too much. I dropped it, so I’m one class short of an English degree. I had a really strong interest in math; I considered law school. I am very capable of a lot of different things and I’m a fast learner, but I have to still do art. If I don’t do art, I can’t do the other things.

AJL: It sounds like you could have taken various paths, but you sought out art graduate school. Tell me more about that journey.

AG: I went into non profit art administration for a long time. Then I had lunch with one of my old professors and she said, “Honey, you are not gonna be happy with this; you need to go do your MFA.”

But I left undergrad not knowing shit about shit. I applied to a bunch of grad schools. I got into the Museum School in Boston and did that for a year, and got my ass handed to me. I felt like the biggest country bumpkin. I believed in what I was making and didn’t struggle to make things, but I didn’t know how to talk about them, and I think people thought I was an idiot. Then I applied to grad schools again. I went to Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) and I put myself on my high horse and thought they were idiots! I had a miserable time for a year, but stayed and by the second year I found my people.

I met Michael there. He was done with school and hanging out in Savannah. We started dating and Savannah was a really beautiful place to be in love — Spanish moss, open cup rules, the beach is right there. But it’s twisted too, really fucked up in terms of the haves and the have nots. So, I finished my thesis and said to Michael “I’m going to New York.” At first, I got a shitty apartment in Crown Heights; I’m pretty sure my landlady was being evicted. Then I sublet from some artist who was in Berlin and took care of her diabetic cat. Then Michael and some friends came and we all moved in together.

AJL: OK, let’s get into your work. I love the fact that you are such a warm, open person and yet your work is sardonic to the point of cynicism about human nature. Where does this dichotomy come from?

AG: Scout has this children’s book about Michelle Obama and one thing in it is about how first you get them to laugh, then you get them to listen. That’s so right. There’s an honesty in that voice and we should probably all embrace the dynamism in our character.

I come from a long line of English teachers, readers and storytellers — ingredients for any good story are layers. As a kid I used to dig in the garbage, my mum didn’t give me a lot of toys. What Scout had at a Waldorf school, I had the Tennessee version of that! In the dirt. I would find old onions and sit in the pantry and peel layers off onions, and it was so satisfying. The outside would be so gross and slimy, and inside there was still a fine little onion that you could still use. It’s a great metaphor for the complexity of human beings. And I love true crime. I can tell you every murder story; how can something be so twisted, how does a human brain get to that place. It’s fascinating.

AJL: Words feature heavily in your art; often quite explicit phrases. Why is that?

AG: Words have always been present in my artwork, even in canvases from when I was a kid. My real calling is that I want to be a writer, but I’m terrified, because someone critiquing my writing is like stabbing me. So if I can take just a little bit and paint it — you can criticize my choices of color, forms, whatever; but you can can’t cut the words, that hurts.

The language is the golden nugget, the thing I’m most interested in. Words are raw and meaningful, and dynamic. Expressing yourself with words is one of the most tender and vulnerable things you can do.

AJL: Your work is so beautifully detailed. I found it hard to tell if it was created by hand. Tell me more about your process.

AG: I work in these really defined series. The bad thing about that is they take forever. I need to come in and be in my own room, just sit sometimes, sit on the floor and look at a weird corner, so it's really unfortunate that it takes so long — not good for an active career, but good for my heart.

The first thing I do is get gesso on the paper. I love how ink comes down on gessoed paper. The whole thing that happens is the words — they often come when I’m walking, the tempo of walking allows words to come to me, sometimes free writing until I pull out one sentence. Then I sit down and doodle for a long time, exploring symbolic references from the sentence itself. Then I get into palette and design.

There’s an ink wash at the back. It’s all hand drawn. It looks precise but there are little imperfections, which I like because I like to be able to see the hand. The text and diagrams are done at the end and I try to weave them in.

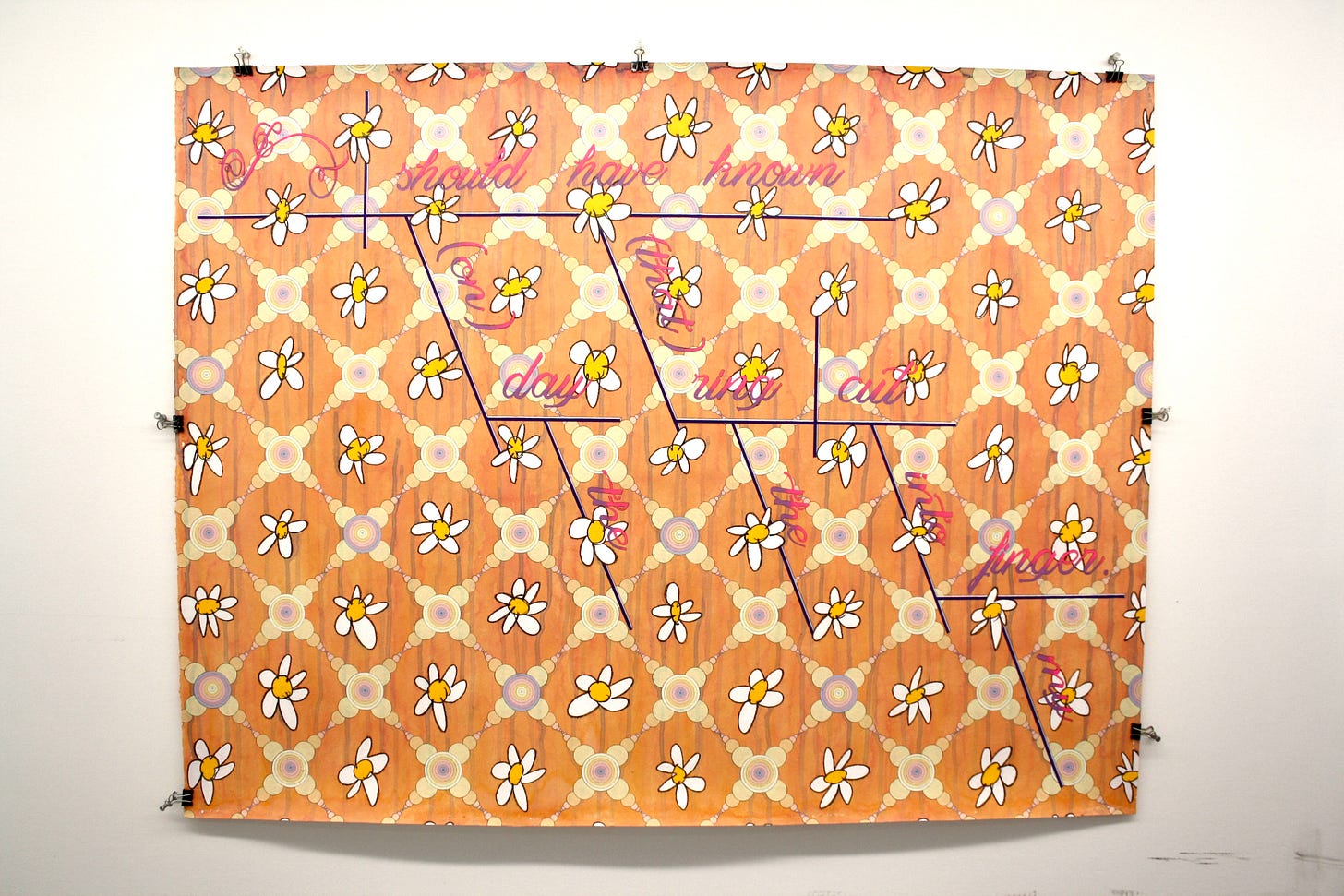

AJL: The physical form of the sentences is really unusual in this current series. Where does that come from?

AG: It’s the Reed-Kellogg Method of sentence diagram — how to learn grammar, what modifies what, conjunctions etc.

So this one: ‘I should have known on the day the ring cut into my finger.’ I am hormonal and about once a month I think we’re gonna get divorced. My wedding band was literally cutting into my finger, and I thought ‘This must mean something!’ The daisies were our wedding flower. I rarely do anything free by hand but I wanted the daisies to have a cartoonish-ness to them, which is a nod to Michael’s work. The seven rings represent that around the seven year mark we had a really hard time. It makes you go in and out, like the rocking you do when you’re really scared. I’m not a super abstract thinker so I like to have reasoning for everything.

AJL: It sounds precise and controlled. Is that hard to maintain?

AG: At 45 years old, I’m trying to find that balance between perfection and mistake. And I’m trying to let the mistake side be the more honest, valuable, worthy side. Perfection is exhausting and not worth it because so few people notice it. Things that we think are mistakes can be perceived as perfection by someone else. So, if my hand slips, I can think ‘leave it’... even if I come back later and fix it.

AJL: Your Provenance Label Series is paintings of overheard snippets in art galleries. You said in a previous interview that those people were candid in front of you because, as a framer in the gallery at the time, you were essentially invisible to them. Do you feel seen by the art world now?

AG: It is such a world of characters. In the art world, the ego has to be everything; it’s your existence, it’s so fragile but it’s so eager.

We sold some of that series to the people who are featured in the paintings! You stroke the ego for a hot second and you can go. One got me in trouble — Susan Inglett called the gallery and told them to take the piece down; the director said “We’re not taking it down. they’re all directly overhead quotes.” Sometimes people were saying things about friends of mine. It’s so callous.

They’ve sort of morphed into this really interesting snapshot of the gallery scene in the early aughts, before the gallery world truly exploded — there were these mid tier galleries, and many of the artists they are referencing are now auction house darlings. It’s data collection.

AJL: There are other prominent artists that feature the written words in their work, like Jenny Holzer. Who are the artists that most inspire your work?

AG: Good question. Glenn Ligon one of my absolute favorites forever and ever. Robert Ryman. I was in a show with Jenny Holzer once — that was a dream existence and experience. I love Sophie Calle, the French artist; she is a poet.

And Michael. We never work in the same space together — he thinks I’m really messy. The benefit of being a partner in this way is brutal honesty. I can walk into his room and say ‘Babe this is not finished.’ It’s good to have that push, even if he ignores me. He comes in and helps me solve problems I don't even realize I have, in a really interesting way. I trust him completely. He’s really good with color. He also has a really great line — when he makes a mark I like the mark his hand makes. He can come in here and look at my line and say ‘That needs to be a little thinner.’ He understands the subtlety of visual communications.

AJL: You built this studio together. How has moving to the Hudson Valley impacted you as an artist?

AG: We moved up here because Greenpoint was changing so much and we realized we could have a house and land. We’ve been here for eight years. We were here less than a year before I got pregnant. A year and a half of baby time then the pandemic hit. I feel at home here now. And I still love the city — I loved that all the freaks belong there, and New York City is the first place I felt I belonged.

I think a lot about how motherhood affects this stuff. I’m not forcing it — I don’t want to make art about motherhood unless it comes to me. It’s not about how Scout affects my work, more about how this life affects her. We were at the Ronald Mcdonald house during her surgery. She’s never had a McDonalds, but she’s been to MoMA, the Guggenheim, and so on. So she’s like [pointing at the Ronald McDonald sculpture], “What’s that pop art sculpture out here?” I like that for her.

AJL: I love that for her too. Thank you, Alex. I could talk for hours, but I want to give you back your morning. Before I go, what are you working on right now?

AG: This piece I’m in the middle of right here. I haven’t touched it since April. I’m excited to get back to it. These are Scout’s IV bags and the drip. I’ve been playing with a phrase: ‘I felt our world shatter like windshields and sculls in a midnight catastrophe.’

We talk about a lot of this, responding to the immediacy. Do we want to give it fuel? But creating art is creating cultural history. We’re aware of how to incorporate it honestly. I don’t want to have to avoid it. It has to come on my walks. Maybe when there’s a cure [to Scout’s condition] I’ll be ready to make art about this period. I process everything here in the studio — being in a space where I can dig to the deepest, darkest, most fearsome parts of myself. I love having that mandate.

Tis the season: if you want sweet gifts made locally, visit the Wren House Goods pop up next door to Bluebird Wineshop in Accord, NY — open till December 22nd.