“Doodling with sandcastles had some physical effect on me”

Edition 43: An interview with artist Joyce Robins

I want to tell you a story about a girl named Joyce Robins. At 19 years old, Joyce is fully grown but barely five feet tall; wearing a mini dress with opaque tights. She is shy and deadpan funny. It’s the mid 1960s in Manhattan and Joyce works serving hash browns to Andy Warhol and his crew at Max’s Kansas City. But Joyce is in New York to be an artist, studying at Cooper Union. She creates bold abstract sculptures and paintings — inspired by the beach in the Rockaways where she grew up, yet alive in the cement buzz of the city. This pint-sized girl from Queens puts on shows in abandoned stores in Soho with Louise Bourgeois, gets advice from Sol LeWitt who lives down the street, and fends off advances from curators and professors left and right.

Despite herself, Joyce falls in love with Tom: a towering painter from the year above. He is fearless and articulate, she is quiet and instinctive. Their lives and work become irretrievably intertwined. What they share is what we all want: True love. Joyce and Tom create art alongside each other and fill their home with pieces by talented friends. They raise their son, Casimir, in a converted temple with 22 feet ceilings on the Lower East Side. They buy a house upstate where Joyce can exercise her green fingers, and watch movies together every night, plucked from a library meticulously catalogued by Tom. They hike the Shawangunk ridge, with Tom always a few impatient, longer paces ahead of Joyce.

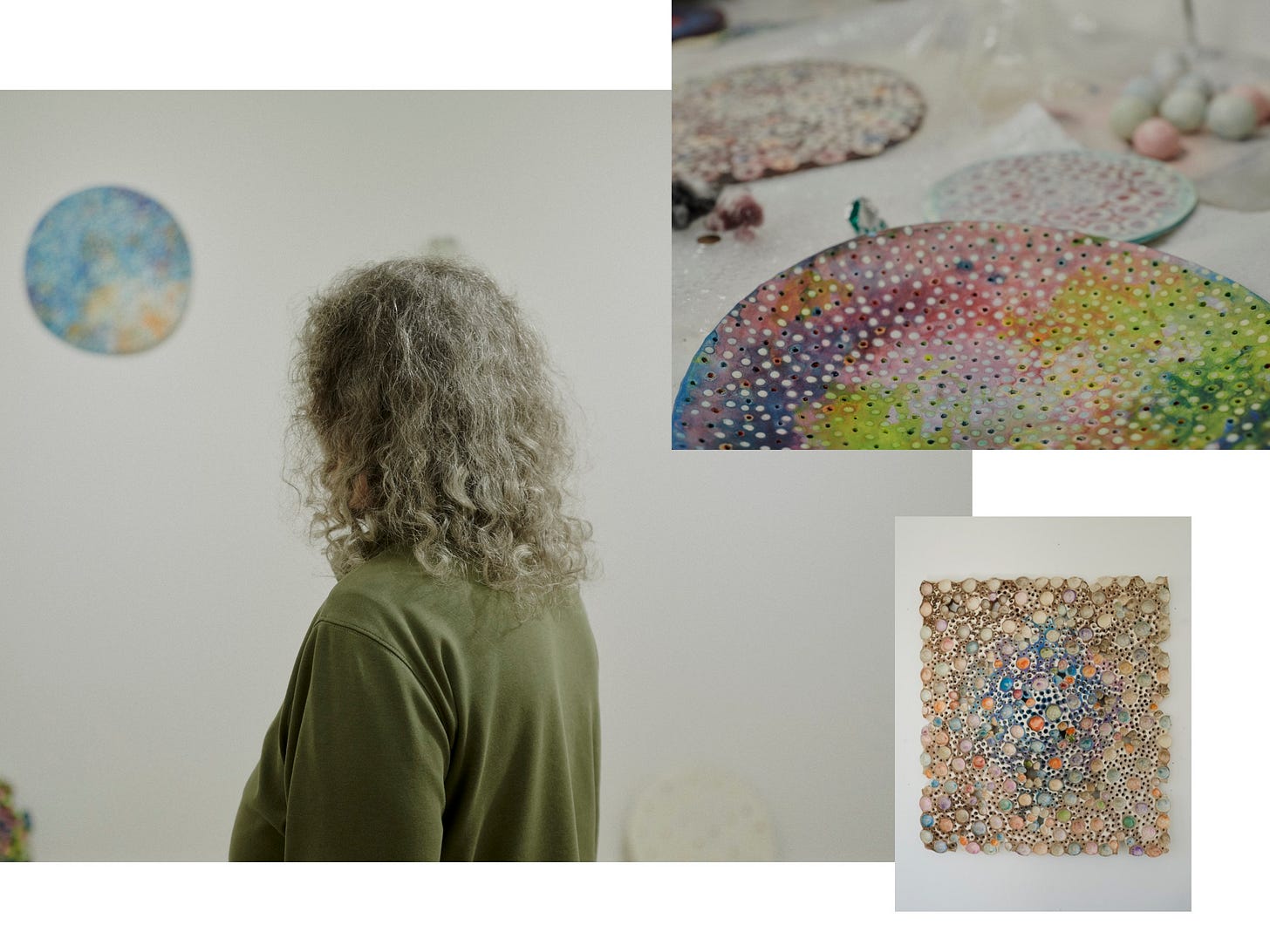

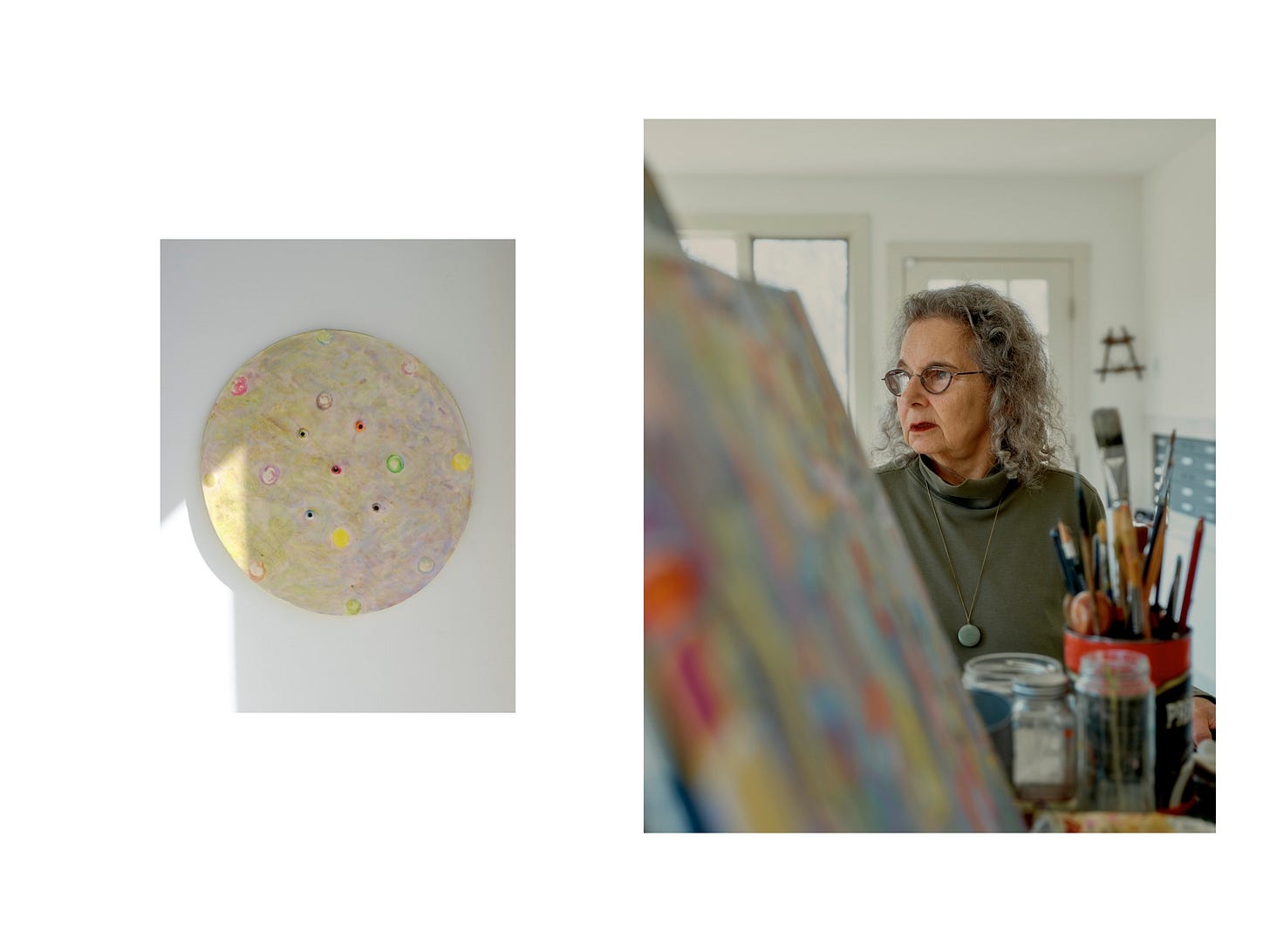

Over time, Joyce creates a remarkable body of sculpture and paintings, each piece beautifully weird and intergalactic and ocean-like in their tactility, detailed colors and strange shapes. But, like the plants she nurtures in her garden on the hill, there is only so much sun to go around: While Tom’s work is celebrated globally, Joyce’s brilliance becomes more hidden. Her sculptures curve and peel from the walls of an underground space below their converted barn, like a dazzling reef waiting to be discovered.

Then in 2019 Tom dies, too soon, and Joyce is left behind. His loss is huge in every sense. She is surrounded by rooms packed with paintings and half squeezed oil tubes, a loft space full of DVDs and Blu-rays, a lawn that dots with crocuses each spring, sprouting around the metal sculptures Joyce created that catch the sun like a dial, marking the passing of time.

That girl from the Rockaways is 80 years old now. Joyce is learning to live without Tom. She plays old board games and watches Karate Kid with her grandson Rocket. She visits gardens across the Hudson Valley, and friends’ gallery shows in the city. She just renovated the sculpture studio on her High Falls property complete with a modern kiln — preparing to make something new. The forsythia’s and magnolias of spring are emerging, and I believe it is time for the story of Joyce Robins to enter a new chapter: Revelation.

I spent a morning recently with Joyce, talking about her life and work, soaking up all her anecdotes about the New York art scene. My friend and talented photographer, Nyra Lang, joined us to capture Joyce and her work for this piece. Joyce is reluctant to make explicit what inspires her work; in fact, she regularly categorizes her inability to articulate her intentions as a flaw in comparison to her late husband’s verbal dexterity. But I think her work speaks for itself. I hope you enjoy this conversation with an artist in her prime.

AJ Lee: Joyce, take me back to the beginning. I read that you were born in South Carolina, before you moved to the Rockaways, NY. What do you remember about that time?

Joyce Robins: My parents were in South Carolina during the war, my father was flying to Japan. Then the war ended and we moved back to New York. Tom was doing lectures down south once and I said ‘I’ll go have a look around.’ But there was a wonderful garden in Durham I wanted to see, so I forgot about my ancestors and pursued the things I was really interested in.

I was two when I moved to NYC. I grew up in Rockaway. Rockaway was really fun; it has a boardwalk and you could hang out under there if you wanted to have a tryst. When I was young my father had three stores selling children’s clothes, all along 125th Street in Harlem — we always had to work in the stores for the holidays. I worked there when I was in high school and I was friends with all the girls my father employed; so I had an appreciation for Harlem culture.

I work mostly abstractly. I think a lot of it had to do with growing up at the beach. You can sit there and make sandcastles. I was inclined to be making art. It had nothing to do with the environment I was in, except for how the beach and clay and doodling with sand castles had some physical effect on me.

AJL: So, how did you make the leap from beach life to the city?

JR: When I was a pre-teen I started taking the train into the museums. In high school, I had a friend who had an older sister that wanted to be an actress, who had an apartment on 68th street; we could crash there as young teens. I was hanging out, playing baseball with actors in Central Park. It was so exciting. There were a lot of egotistical guys — early actor wannabes, so it was very interesting. It was also frightening.

I was 18 and into the art world and acting in high school; so I was hanging out with older people. As soon as the school week was over I would get into the city and that was great for looking at art.

AJL: You sound curious and quite brave. After High School, you joined Cooper Union, the famous New York art school. Tell me what life was like in NYC then, in the mid ‘60s.

JR: Cooper Union was free at the time for the whole four years. I think it’s really important that kids can go to an art school that’s accessible. Cooper was a very mixed, interesting environment; intense and exciting. It gave me cues to go see things, get involved with the theater, learning from the actors I was becoming friends with.

NYC was incredibly exciting — there was nothing like it. I was wearing short skirts, tights; I was pretty cute in the old days. There were artists who were older than me who were iconic and important; I’d have to look at old diaries to see who the faces were. It was a series of odd romantic encounters, but I was careful.

Basically I was going out and taking the train back to Rockaway at two or three am and my parents were starting to go crazy from that. So I took an apartment in the city and in the summer I got a job as a waitress. I worked at this place: Max’s Kansas City — it was pretty famous at the time. I’d be slinging hash at Andy Warhol. And I was younger than all of those people, and I wasn’t unattractive; and we had to wear a French soubrette. It was a fun and social thing.

AJL: And is that when you met your future husband, Thomas Nozkowski?

JR: I met Tom at Cooper as a freshman; he was a year ahead of me. I didn’t like him. He was always talking, thinking about art and articulate. But I found it frightening. So I avoided him for the first year. He did ask me out but I said ‘Get out of here’ — I was afraid of it. I was afraid that I would be subjugated to some super ego; I wasn’t ready for that, I was timid.

I was a little girl, maybe 5 feet tall, and he was 6’2”. I watched him and wondered but didn’t listen to what he was talking about. Eventually, Tom finally came after me in a way that was romantic and fetching. I said ‘OK’ and we went to Pete's Tavern — that was a big deal to him because he had very little money; the fact that he actually paid signaled to me that this was something worthwhile. So I started to listen to how he talked. And listening turned into love.

Tom had two passions: The art world and making art; and movies. He used to make lists of directors, he was way ahead of it. He knew that was a symbiotic relationship between the two — art and movies. I got into it too. It was a visual thing, supported by a kind of emotional aesthetic. We were thinking about it separately from most of the characters around us; he was really visionary about it.

Once I succumbed, I was extremely happy, and we stayed together for 54 years on the books, plus two years before getting married.

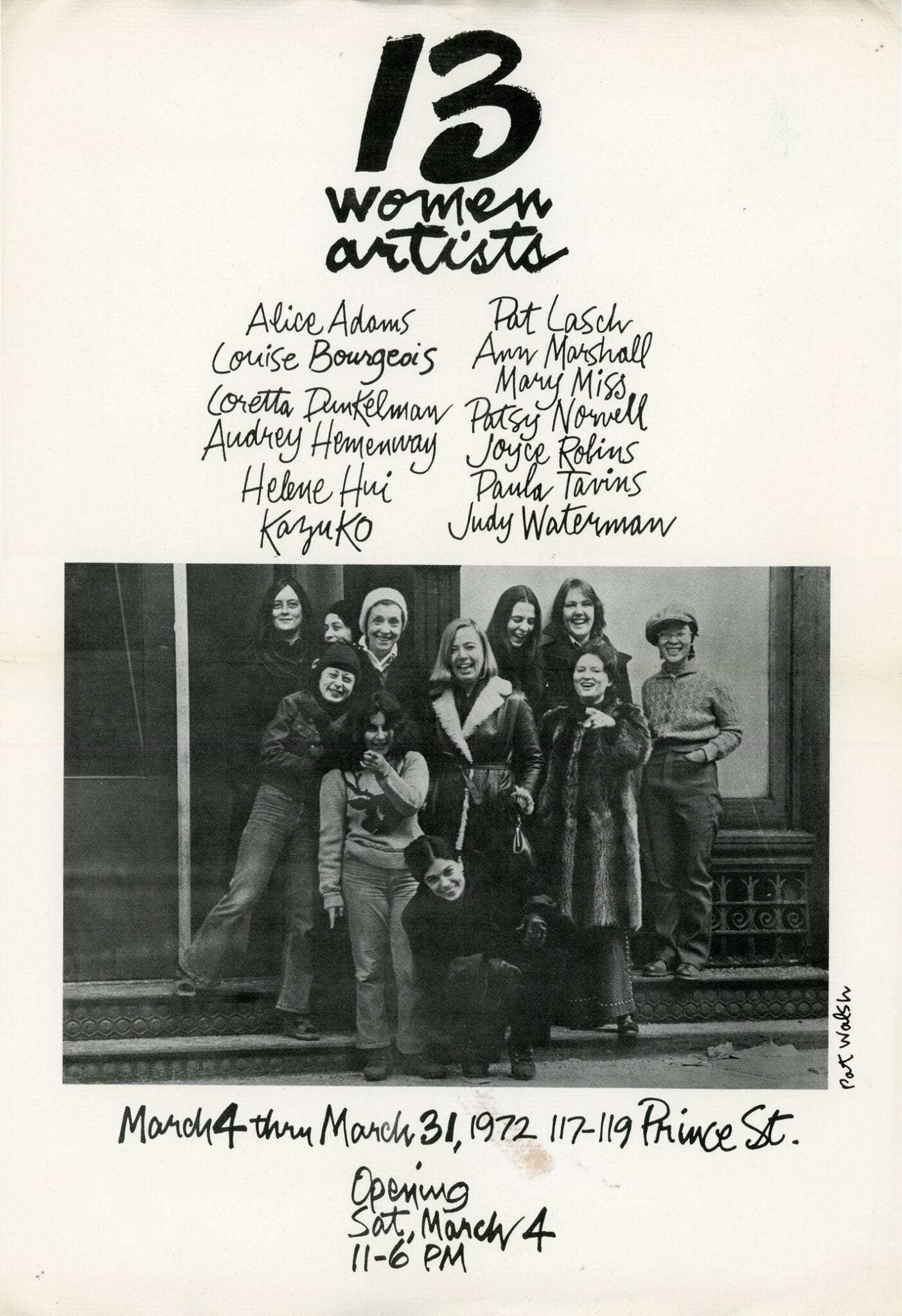

AJL: This was a time when the women’s liberation movement was beginning, and I know you curated a show in 1972 called ‘Thirteen Women’ Artists’. How did that come about?

JR: There was a critic called Lucy Lippard and there was a women’s group evolving just at the time I was getting into Cooper Union. I wasn’t really political — I wasn’t marching or being aggressive. Lucy Lippard was older than me and involved a lot in women’s art. I was part of it in a quieter way. That women’s movement wasn’t really there yet, it was a small idea in a lot of women’s heads.

I had a friend named Ann Marshall, she and I went around and we wanted to get a mix of older and younger women for a show. Louise Bourgeois was married to a curator — she was kind of like me, quiet and unassuming. We said we’re curating this show. I had a former teacher that was in charge of this building in Soho, he had a loft on one of the floors. Basically he was always trying to hit on me, but I asked him if I could rent the space because it was vacant. Louise insisted on painting the floor gray under her sculpture, the night before the opening of the show — it was a piece called Fillette, which was kind of phallic, hanging from the ceiling. People came in and stuck to the floor! But you couldn't scream at her because she was an icon.

AJL: I want to know more about your work. What is your inspiration? Are you conscious of trying to create a particular end effect?

JR: My work is a combination of intuitive and conscious. Once you learn certain things you can see if it’s relevant, you have an idea of whether it’s successful. Look at the rainbow on the wall right now [Joyce gestures at a light effect beside us], that stuff gets absorbed into your mind. The crazy green and the red, that could turn into some sort of painted element. It’s just sensory perception; responding to stuff that’s around.

At Cooper Union I learned how to weld and do sculptural objects. I liked physical things, rather than flat. So I started out with that appreciation of a kind of tactile art. I was never interested in interpreting realistic things, it would always be abstraction that influences me, but probably unconsciously. I don’t have a formula, or a proposition to work from.

It’s like pieces find their place. It’s very unconscious. It just happens. Eventually you see what you’ve done. It’s logical. It’s sort of an emotional thing, like I’m trying to describe what’s happening in my brain. I would just be doing them and not thinking about it. It’s like if you could explain having a feeling about an experience.

Having so many years of a romantic relationship with someone who was pretty impressive was very satisfying, but I didn’t want to compete with it. It’s hard to separate my experiences from Tom. I was living with a giant. I would just be quietly doing this stuff.

AJL: Your ceramics are so organic and distinctive in shape, color and texture. How do you make them?

JR: I don’t think about it verbally — it’s in the act of using the soft material. I find that if you put the holes in the clay beforehand, you give it a sort of strength so it doesn’t crack. I have to punch the holes in it so it doesn’t explode in the firing. I’m working with the restrictions of the material and the heat.

I want them to be moving. You’re working with your fingers. I‘m very happy when I make one that feels like it’s part of the world. I like the fact it can look like a piece of paper flying; and the shadows they create when they come off the wall. [Joyce points to a piece that has organic shaped bricks like vertebrae] This piece you can stack them anyway you want and play with it. I don’t look like a playful character but I seem to be able to do this stuff.

AJL: You have a beautiful spot here on the hillside. What does this part of the countryside mean to you and your work?

JR: We got this place in High Falls in the ‘70s. When Cas was born we were renting a place on Hester Street, a former synagogue, 22ft ceiling to the floor, and it had a horseshoe balcony where I worked. Sol LeWitt lived on the next block. He was friendly but older, he wasn’t into what we’re all about. He introduced me to a woman, a Japanese artist Kazuko Miamoto and we became friends.

Before we bought this place, Tom and I would go hiking on Bear Mountain. We were always into climbing in the woods, climbing the Shawangunks. Tom and I mostly walked together. That’s not true — he was always 20 ft ahead of me, because he’s so tall, galavanting off.

I was always into plants and this was an opportunity to really get involved with it. After my husband passed I tried to accumulate things I like to do, to keep myself from being sad. I spend a lot of time in the yard. I usually clean things up in the spring. This ridge is incredible, it goes all the way to Pennsylvania, there’s caves and all sorts of things. It’s always exciting. I can go around, up this road and get the Catskill view.